…a Scrum Team is working on a single product with multiple Development Teams. The Development Teams need to coordinate dependencies and shared work. Unresolved dependencies within individual teams are a shared challenge of all teams.

✥ ✥ ✥

When multiple teams work independently of each other they tend to focus myopically on their own concerns and lose sight of any common goals.

Organizations might revert to a command-and-control approach in the false belief that agility only works at the scale of one team, but complexity has grown, not diminished, in this circumstance. Hierarchical control increases delays and reduces the responsiveness of the teams and the wider organization to business and technology changes.

The Scrum Team could break the problem into smaller pieces so each Development Team could work separately on part of the deliverable. However, the Taylorist idea [1] that optimizing the whole follows from optimizing each local part does not work in complex environments ([2], and [3]). Unexpected dependencies arise between the work efforts, slowing delivery, and reducing the ability of the organization to respond to change.

The separate teams could coalesce into a single, undifferentiated team but the communication and coordination overhead would grow exponentially, causing informal subgroups to appear, probably along demarcation lines that would mean they were less than cross-functional.

The multiple teams could report to a common manager or management function responsible to resolve dependencies, blockers and other inter-team issues as they arise. That manager would create a master plan to coordinate the Development Teams’ work. However, this approach surrenders the autonomy of the teams, lowers their investment in the product (their sense of having “skin in the game”), reduces responsiveness and flexibility, and limits the learning opportunities that arise during development. Richard Hackman, in his book [4], claims that successful teams are aware of and handle their surroundings themselves, which includes coordinating with other teams. Rosabeth Moss Kanter of the Harvard Business School, in her study of empowerment in the workplace, has written that as the world becomes more disruptive “the number of ‘exceptions’ and change requirements go up, and companies must rely on more and more of their people to make decisions on matters for which a routine response may not exist...” ([5], p. 18). At the same time, experience shows there is genuine autonomy only when teams and individuals accept responsibility—and accountability—for their decision-making. While directions “from above” may create the space for autonomous decision-making, self-governance becomes a reality only when those “below” intend to occupy that space and act on that intention ([6], p. 398).

Self-governing teams are not only more responsive and adaptive to change, they are the only sustainable source of job satisfaction ([7], p. 398). On the other hand, autonomy without alignment can result in each team moving off in its own direction, to the detriment of both the product and the organization ([8]).

Therefore:Give the right and the responsibility to collaborate on delivering common goals identified by the Product Owner to the Development Teams themselves. Permit the teams to figure out the best way to coordinate their efforts.

✥ ✥ ✥

Successful alignment requires that everyone involved in the development, in every team, must have visibility of the product as a whole, its Vision (see Vision) and its goals. This will typically involve expansion of the Product Owner Team to a level judged by the Scrum Team to be appropriate. Development Teams will use some of their capacity to support the Product Owner.

Scaling, when it does occur, is always situational, so the exact forms of collaboration will be determined by the Development Teams, but typical tactics include:

- Sprinting together–at the same cadence, at the same time, using Organizational Sprint Pulse

- Maintaining a common Definition of Done

- Common Sprint Planning, Sprint Reviews and other mandatory Scrum events

- Holding Backlog Refinement events in common

- Creating semi-formal optimizing networks of Birds of a Feather, utilizing common competencies such as architecture across the teams to proactively handle issues that are known in advance

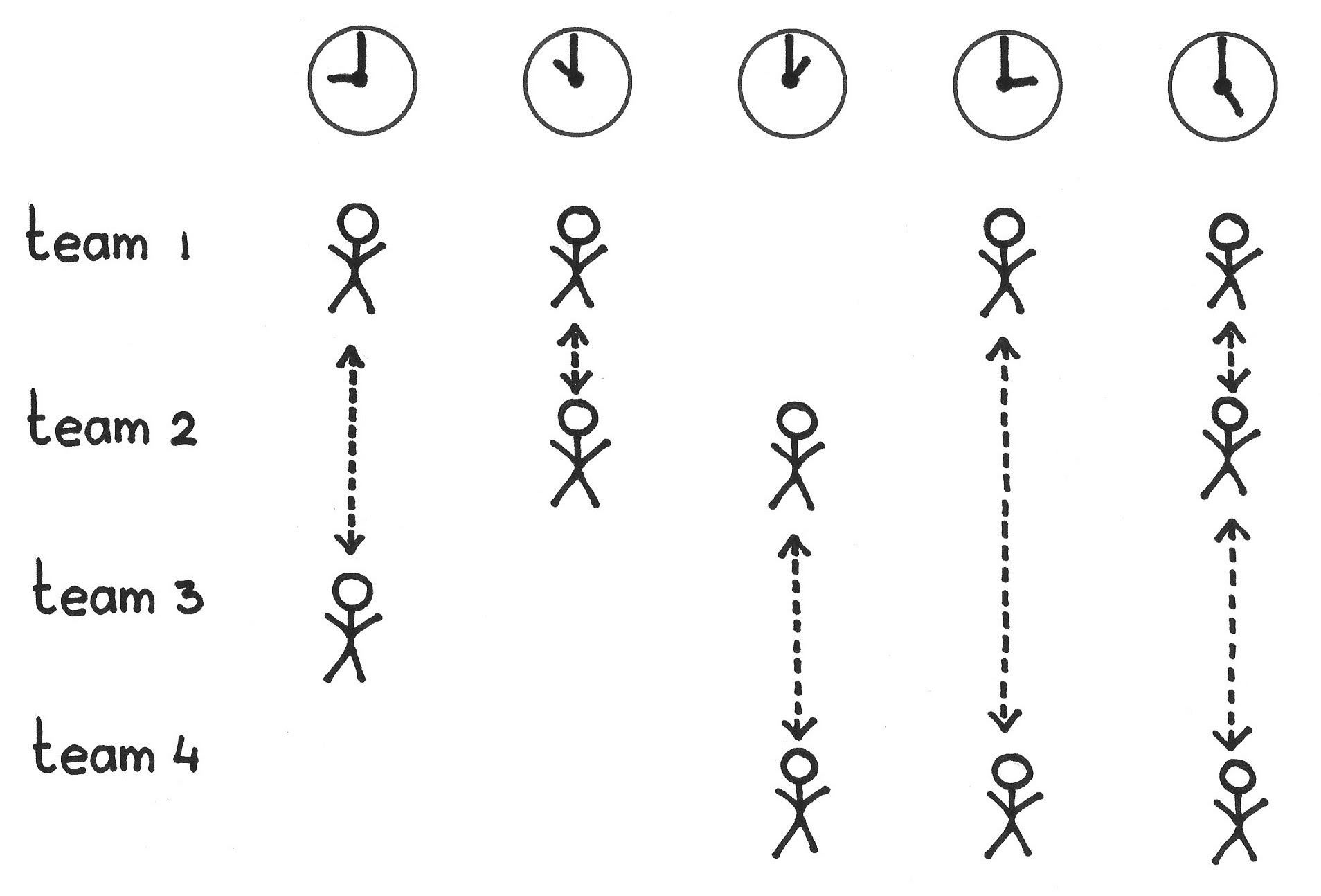

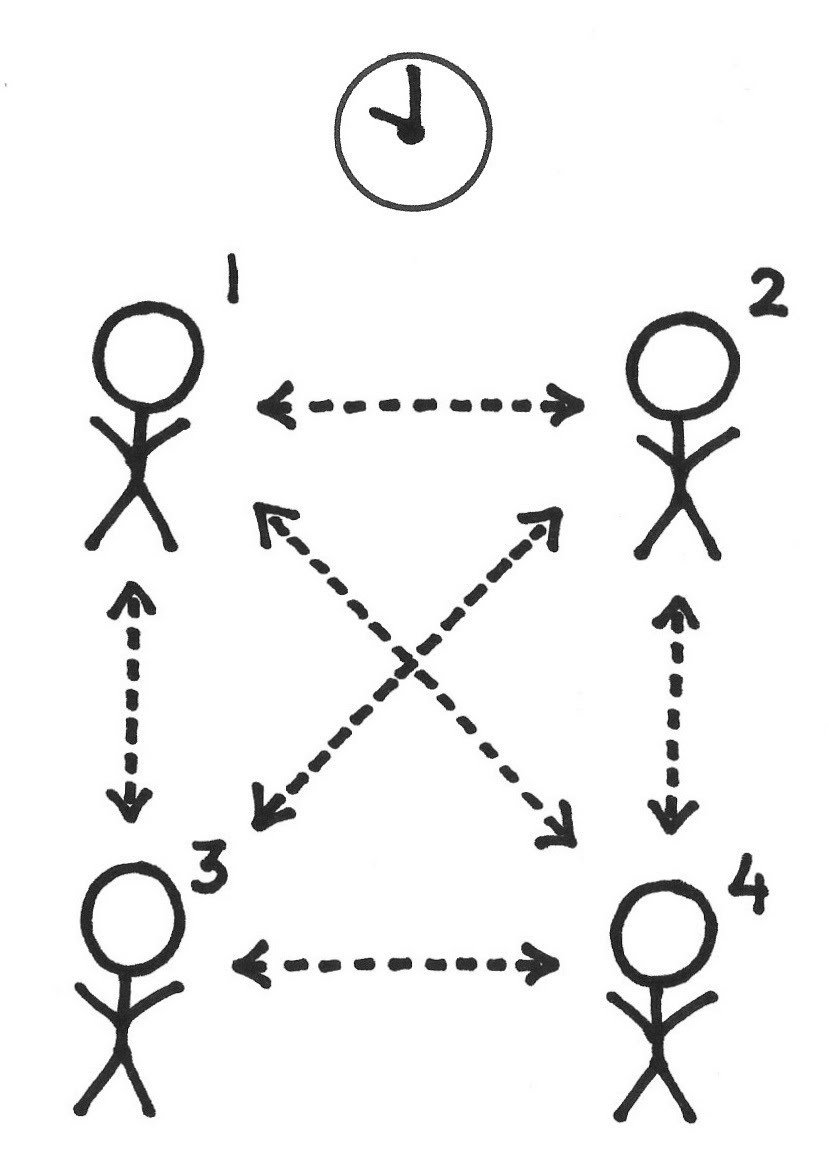

- Establish a regular Scrum of Scrums event, [9] perhaps daily, after the teams’ Daily Scrum events, to resolve emergent dependencies and issues, and to get things to Done (see Definition of Done).

Whatever the formal arrangements for coordinating dependencies and discussing impediments, the teams should not postpone resolving them to the Scrum of Scrums. The teams work on the impediments as they emerge. When teams need to coordinate, the teams can just talk to each other without waiting for the next meeting on the schedule. Development Teams organize themselves to get their work Done and minimize dependency risk using Dependencies First. The ScrumMasters help to remove impediments to the Development Team’s progress, and teams can invoke the Emergency Procedure as a last resort. It is the level of spontaneous interaction and unscripted collaboration between teams and their members that is the true measure of the effectiveness of the Scrum of Scrums.

Teams and their members should bring issues to the Scrum of Scrums out of Product Pride rather than out of fear or even duty.

The Scrum of Scrums is a well-established pattern, first implemented at IDX Systems (now GE Healthcare) in 1996. Jeff Sutherland was Senior Vice-President of Engineering, with Ken Schwaber on board as a consultant to help roll out Scrum. There were eight business units, each with multiple product lines. Each product had its own Scrum of Scrums. Some products had multiple Scrum of Scrums with a higher level Scrum of Scrums. Every product had to deliver to the market with a release cycle of three months or less and all products had to be fully integrated, upgraded, and deployed every six months to support regional healthcare providers like the Stanford Health System. It is clear from this example that there may be multiple, even parallel Scrum of Scrums and even that a daily Scrum of Scrums (considered as an event) can split into sub-meetings with separate foci. The first publication mentioning Scrum of Scrums was in 2001 ([10]) and it also appeared in the Scrum Papers [11] in 2011.

[1] Frederick Winslow Taylor. Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Harper, 1923.

[2] Thomas F. Burgess. “Making the Leap to Agility: Defining and Achieving Agile Manufacturing through Business Process Redesign and Business Network Redesign.” In International Journal of Operations and Production Management 14(11), 1994, pp. 23-24.

[3] Claude R. Duguay, Sylvain Landry and Frederico Pasin. “From Mass Production to Flexible/Agile Production.” In International Journal of Operations and Production Management 17(12), 1997, pp. 1183-1195.

[4] Richard Hackman. Leading Teams, 1st Edition. In Harvard Business Review Press, July 15, 2002.

[5] Rosabeth Moss Kanter. Change Masters: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the American Corporation. New York: Touchstone 1984, p. 18.

[6] Daniel Katz and Robert Luis Kahn. The Social Psychology of Organizations. New Jersey. John Wiley and Sons, 1966.

[7] Christopher Alexander, Sarah Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein with Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King and Shlomo Angel. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977, p. 398.

[8] Charles Heckscher. “The Limits of Participatory Management.” In Across The Board 54, November-December 1995, pp. 14-21.

[9] The Scrum of Scrums as a daily meeting of ‘ambassadors’ from multiple teams is described on the Agile Alliance website. https://www.agilealliance.org/glossary/scrum-of-scrums/.

[10] Jeff Sutherland. “Agile Can Scale: Inventing and Reinventing SCRUM in Five Companies.” In Cutter IT Journal: The Great Methodology Debate, Part 1 14(12), December 2001, pp. 5-11.

[11] Jeff Sutherland. The Scrum Papers, http://scruminc.com/scrumpapers.pdf (accessed 11 January 2017), no permalink, draft, 29 January, 2011.

Picture credits: Greg Neate, http://www.flickr.com/photos/neate_photos/3522905573/in/album-72157617918428883, (under CC BY 2.0 license).