The team had been doing Scrum for a long time now and its velocity had stabilized around 100, running one-week Sprints. Summer was coming around and Sue, one of the five team members, was about to go on vacation. Sue was there for Sprint Planning on the last day before her vacation started. The team was trying to determine its forecast for the next Sprint. “Sue is going to be gone,” said Dan Blooming, the ScrumMaster, “so we should reduce our velocity to 80.” Everyone nodded in agreement. “But we should also try this new kaizen of pair programming.''

A week later, when the team finished, they had completed 120 estimation points of work! They went ahead into the next Sprint and completed 100 estimation points of work.

On Friday, the last day of that Sprint, the team was doing Sprint planning, knowing that Sue would be returning Monday. Another team member, Jim, asked: “What should the team use as its velocity for forecasting the next Sprint’s delivery?”

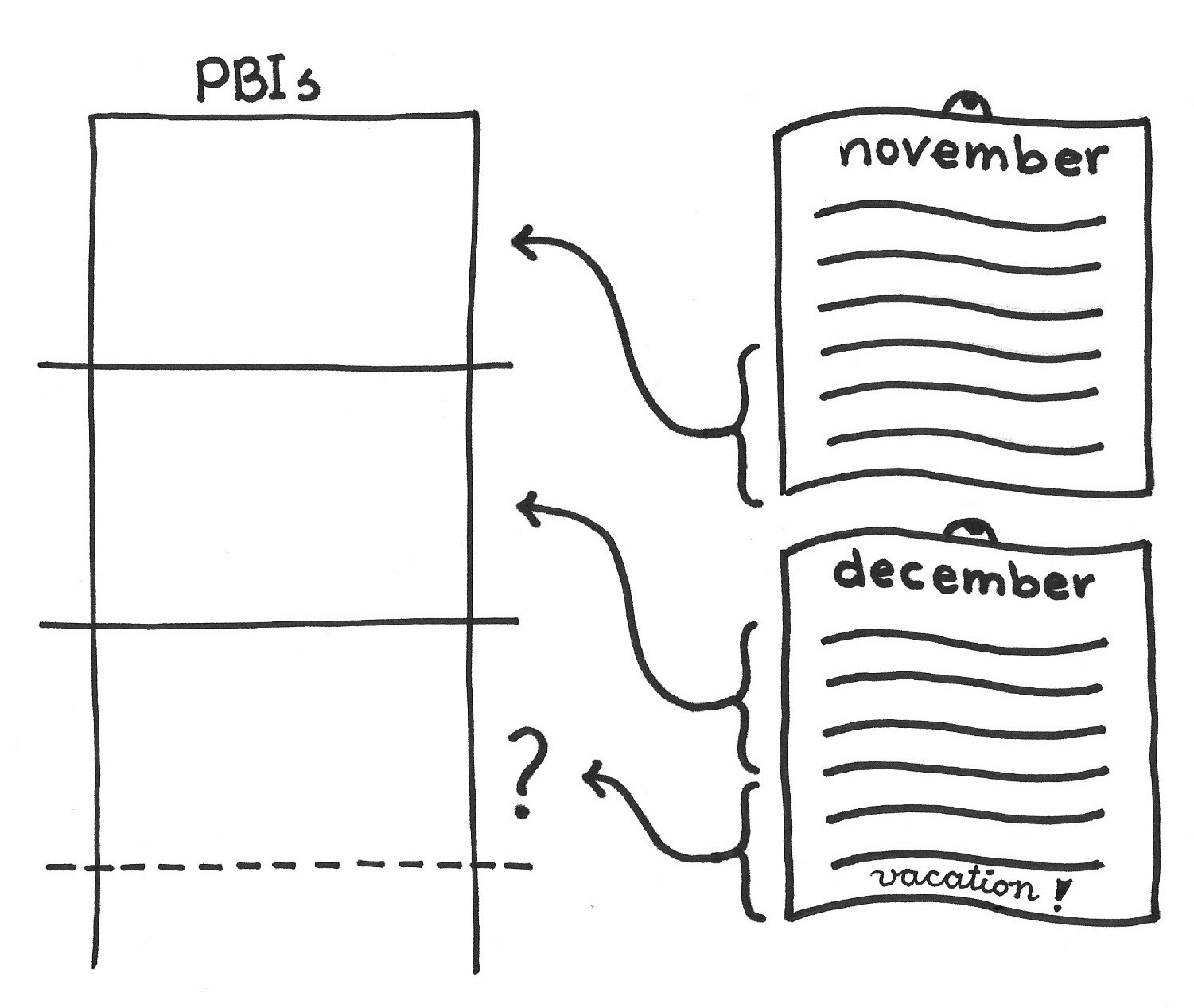

...your Product Backlog tracks the delivery order of value increments to the market. Sprint Planning has to accommodate vacation, family leave, anticipated medical leave, and even team outings, all of which take time away from development but are traditionally respected by corporate human resources culture. These activities affect delivered value directly and costs indirectly. Unlike work on Product Increments, for which Product Owners can schedule the Development Team solely with respect to business considerations, vacations and other “personal” events are sometimes beyond their control (see Fixed-Date PBI). Medical leave and long-term competence development often fit in this same category.

The Scrum Team must be working in a Community of Trust (see Community of Trust).

✥ ✥ ✥

Most corporations honor vacation time and other planned time off for employees, and in that sense, allowing employees to take a break from work is a part of the corporate value system. However, they don’t create market value in the same way that product increments do: the value lies outside traditional value streams. Therefore, it is common for Project Managers who become ScrumMasters or Product Owners to view vacations and other planned off time as impediments, as contributing negative value, or as “special cases” outside financial business value. For example, some teams may view vacation as a human resources concern outside the scope of development scheduling. Of course, that’s unrealistic from a scheduling perspective, so it becomes necessary to plan staffing around planned absences. Many Development Teams adjust their forecast velocity (see Notes on Velocity) downward to compensate for anticipated absences, only to restore it on the individuals’ return.

A team can use Scrum to optimize any value. Hall ([1]) broadens value to encompass the economic, casuistic, and psychological theories of value. The Scrum Team usually ignores vacation and training as contributors to the casuistic theory of value when making the Product Backlog. Usually, only items from the economic theory of value make it onto the Product Backlog. Workers in particular respond at least as strongly to the casuistic theory of value as to monetary rewards ([2]) and, of course, the psychological theory of value is crucial in a work environment. Some of the most highly valued items on professional Scrum Teams lack representation on the major organ of value.

The Development Team wants to meet its forecast regularly, and you want the Developers to regularly stay on a kaizen path that sees both predictability and capacity for work increase over time. The team uses velocity for both of these. And while velocity is not a strict predictor either of value (see Value and ROI) or of efficiency, it is the central empirical measure of the Development Team’s capacity both to predict and complete work.

Being shorthanded reduces what the team can deliver in a Sprint. While vacation absence is a small fraction of the year in the United States, the U.S. is also the only country in the world without a single legally required paid holiday ([3]). Austrians take 35 paid days off each year: about 15 percent of the work year. If you combine these absences with conference attendance, continuing education, and other activities that don’t contribute directly to the product, as much as 20 percent of the budget goes to activities that the business funds only “in the margins.” (“Twenty percent” is a hypothetical figure based on 35 paid days off and about 12 days for training, conferences, corporate social activities, travel, medical leave, and so forth.) And during the summer or around winter holidays, the majority of the Developers may disappear together for up to a month. It’s important to give visibility to how that effects deliverables.

Scrum is an empirical framework that derives velocity empirically according to Yesterday’s Weather. A good Development Team tracks its velocity over time, focusing first on reducing its variance and secondly on occasionally increasing it through kaizen. Adjusting the velocity downward to compensate for an absence destroys the empirical nature of velocity, and can lead to complex, arbitrary compensations for scheduling as often found in Project Management. Scrum has no facility for “remembering” adjustments to velocity, and has no need to “remember” velocity: one can always derive it from empirical data. So a manual velocity adjustment would add a new Scrum artifact. The arbitrariness of a calculated velocity leaves the Developers without any sense of responsibility to meet their forecast.

Therefore:

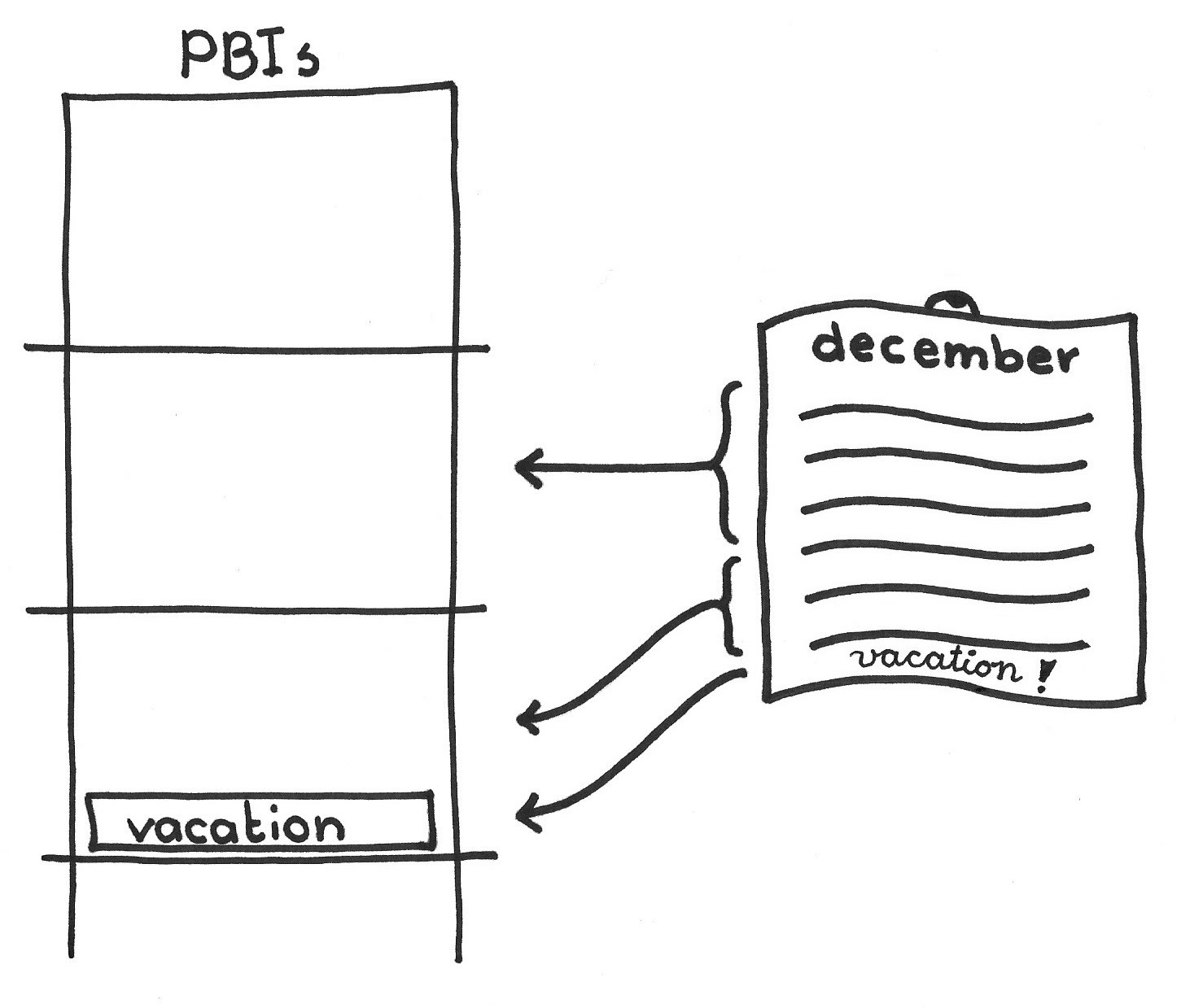

Track planned Development Team member absences as Product Backlog Items (PBIs). Let the Development Team estimate the cost of the PBI depending on the specifics of the absence and of the Sprint in which it will occur. The Product Owner may choose to ascribe a corresponding value (ROI or other) to the PBI as well, corresponding to the value to the enterprise of giving people paid leave from work.

As is true with any manipulation of the Product Backlog, the Product Owner should frequently adjust the relative position of the Vacation PBI in the backlog so it falls in the Sprint commensurate with the fixed date (see Fixed-Date PBI).

✥ ✥ ✥

This will cause the Sprint Backlog content to more accurately reflect the expenditure of Development Team members’ time during the Sprint.

One could analytically ascribe a cost to such PBIs based on the Development Team size, its velocity, and the absence duration. However, Development Team performance is rarely linear in the number of available team members. Different team members perform differently, but more important, an effective team works as a gestalt whose members multiply each other’s effectiveness rather than just linearly adding to each others’ contributions. This is why we let the Development Team estimate instead of using typical Project Management calculations. The common practice of letting the Product Owner (or even the team) adjust the velocity mechanically falls into this trap. There are further subtleties that the team estimation can accommodate. For example, adjusting merely for the absence of a Development Team member doesn’t acknowledge the effort of reintegrating a member into the team on return: he or she must catch up with changes in the implementation, organization, market, and requirements that have transpired in the mean time.

Given these realities, the pattern has limitations in how it affects the accuracy of the Sprint forecast. Nonetheless, first, it directly supports the following Scrum principles:

- The effect of the vacation both on the forecast and on the Sprint results lies in the hands of those who can control the consequences: the Developers.

- Velocity continues to be an empirical measure instead of being subject to special case adjustments or sophisticated calculations.

- We honor the value of transparency: one need only look at the Product Backlog to understand why an unchanged velocity will result in a smaller product increment in a given Sprint.

- This pattern ascribes explicit value to the planned absences that are germane to human beings in a work setting, in a way that honors the value to the individual on a par with the value accorded product increments.

Second, it is better than nothing: the situation is no better if the Product Owner or Development Team adjusts the velocity downward for absences. In the end, the Development Team owns the estimates: putting the velocity figure in the hands of someone other than a Pig takes away the Development Team’s sense of commitment (see Pigs Estimate).

This pattern is of course a two-edged sword, and each culture will modulate the boundaries of application of this pattern. It’s important to ponder the stipulation that the Product Owner can neither schedule nor refuse personal absences that are traditionally matters of personal employee choice and discretion. Some cultures may give Product Owners leeway in allowing or disallowing activities such as conference attendance (though vacation in particular is outside the Product Owner’s purview.) We use vacation as the exemplary case in this pattern to emphasize the Scrum principles above.

Another challenge exposed by this pattern is the awkwardness of publicly estimating individual contribution. It may insult Jim if Sue’s vacation reduces velocity by 30, and Jim’s vacation reduces velocity by 20. In practice the identity of the individual isn’t the only factor in sizing such cost; for example, different technology mixes in a Sprint lead to variance in the cost of different individuals’ absences, as do other variations. In any case, the Development Team will realize a change in velocity during a team member absence, and that will lead to the same issue of quantifying the value of the individual to the team. The fact is that the natural variance in velocity is likely to overshadow variances in the identity of the person absent, and it is unlikely that there are enough data to make any statistically significant judgment about such costs. Perception is everything; however, the ScrumMaster must educate the Scrum Team that variance in the estimation of a Vacation PBI is natural.

Some have argued that this is a complicated or overly long pattern. While the arguments are intricate, the solution is not. The traditions against such common-sense approaches are strong, which is why the forces here are sometimes hard.

These arguments and adjustments aside, the ceremonial inclusion of such absences on the Product Backlog makes visible that care for the personal well-being of team members (through vacation, medical care, etc.) is indeed part of the corporate value proposition. It shows that management cares. Management sympathy or empathy has empirically increased productivity [4] while disdain for such personal concerns can demotivate the team or build resentment. This is all within the Scrum spirit of extending the notion of value beyond the product, into concern for the team and its people, as exemplified in the mission statement of Toyota’s NUMMI plant: ([5], p. 80)

- As an American company, contribute to the economic growth of the community and the United States.

- As an independent company, contribute to the stability and well-being of team members.

- As a Toyota group company, contribute to the overall growth of Toyota by adding value to our customers.

Regarding transparency, the Product Backlog is an established information radiator and organ of transparency in the Scrum culture. Making extraordinary absences into PBIs takes away their extraordinariness; all necessary information is transparent. Any local adaptation of a Sprint velocity complicates the bookkeeping of velocity because it means keeping a history (“undo stack”) of such adjustments that someone must process when the absence is over.

This approach is one example of using the Product Backlog for value concerns beyond what product increments yield for the corporation. Treating such absences as PBIs also makes visible on the Product Backlog approximately when and how the absence will affect the inclusion of individual product increments in projected releases. If the Development Team adjusts the Sprint velocity instead, then each Sprint has a custom velocity, and that seriously complicates the predictions provided by simple, manual tools as well as by more sophisticated computer-aided tools. These complications make the Product Backlogs unwieldy to interpret.

Note that this pattern does not apply to unplanned Sprint interruptions such as incidental sickness or unanticipated business-condition changes. Those are stochastic quantities that fall within the concept of drag (activities that displace time working on the product, thus causing the real velocity to decrease). In the worst case, the team addresses such interruptions with Emergency Procedure.

After learning the Vacation PBI pattern, time came around for Asaf to go on vacation. While the team was striving to become more cross-functional, Asaf did most of the database work when it came up. There wasn’t going to be much database work this Sprint, so the “bus factor” of Asaf being away wasn’t very severe. Asaf and the rest of the team agreed to assess the cost of Asaf’s absence at 15 points, so they created a 15-point PBI. During the Sprint, they burned down a proportional amount each day. The team missed their forecast by five points—well within the statistical norm of a healthy team’s velocity. So the team didn’t adjust its velocity, and carried on without any Vacation PBIs when Asaf returned.

[1] Arthur David Hall. A Methodology for Systems Engineering. New York: Van Nostrand, 1962.

[2] Daniel Pink. Drive: The amazing truth about what motivates us. New York: Riverhead Books, 2011.

[3] Alexander E. M. Hess. “On holiday: Countries with the most vacation days.” In USA Today, 8 June 2013.

[4] —. “Hawthorne Effect: interpretation and criticism.” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawthorne_effect#Interpretation_and_criticism, May, 2018 (accessed 8 June 2018).

[5] Jeffrey Liker. The Toyota Way. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980, p. 80.

Picture credits: Image Provided by PresenterMedia.com.