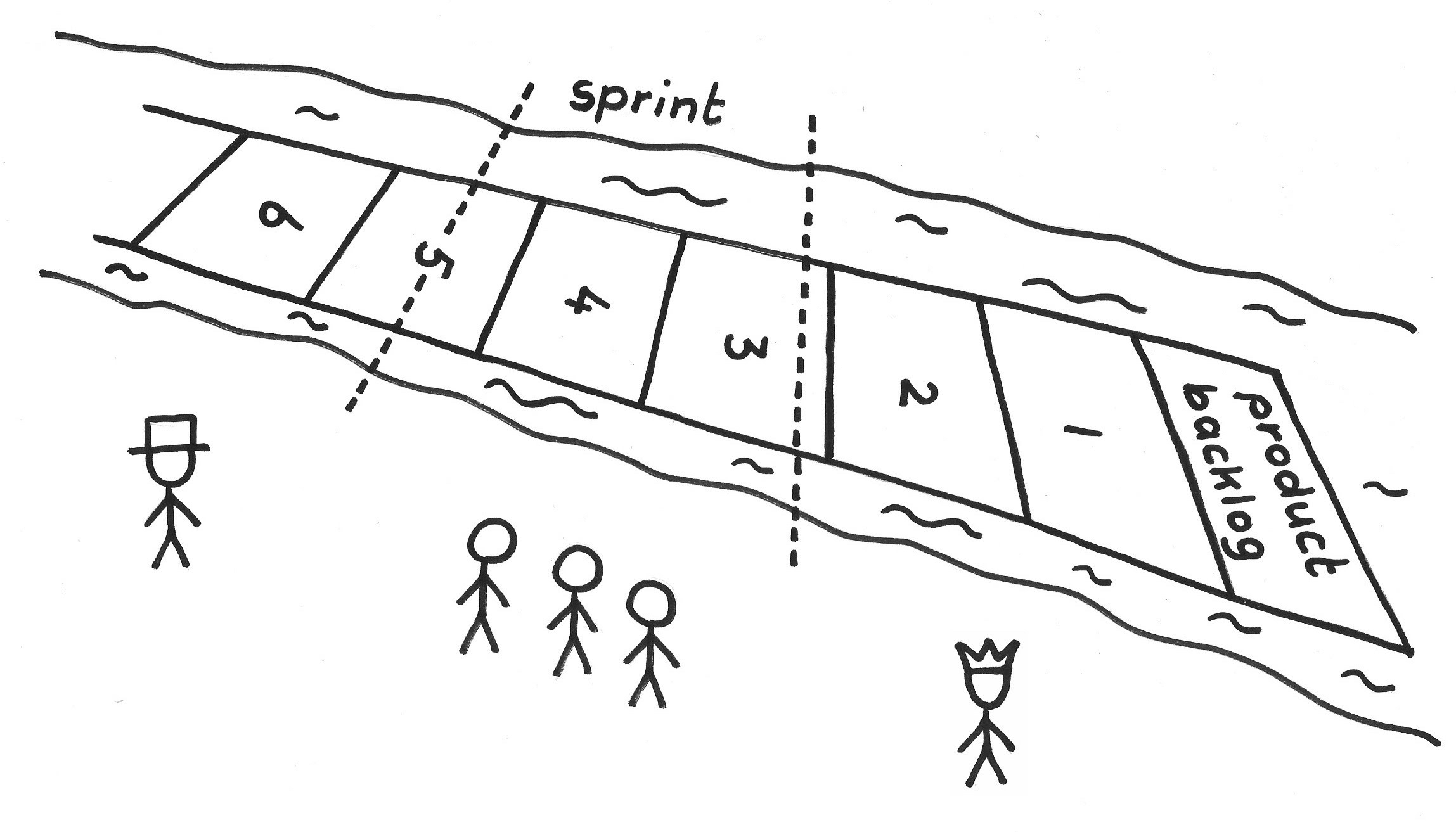

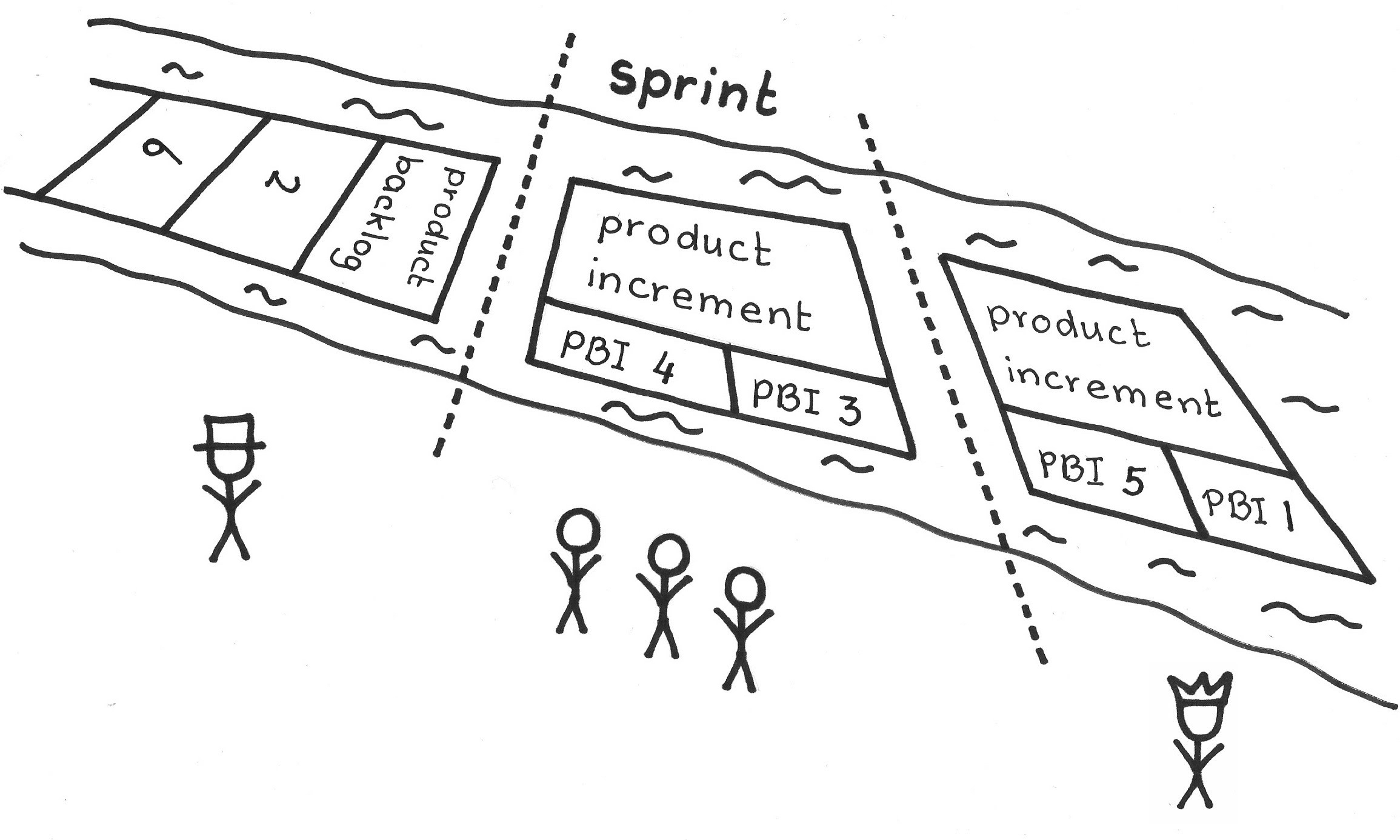

…now that the team has defined and refined the Product Backlog, the Product Backlog Items (PBIs) still represent only potential value. They can produce value (i.e., move to the end of the Value Stream) only when development makes them real. You are ready to embark on a Sprint to develop one or more PBIs to create a Potentially Shippable Product Increment.

✥ ✥ ✥

A Sprint should produce a Potentially Shippable Product Increment. Yet simply pulling PBIs off the top of the Product Backlog does not necessarily result in work that creates the Greatest Value or work that fits into the Sprint’s time box to produce the product increment.

It would be nice to just work from the top of the Product Backlog without worrying about the work ordering, but there are several reasons that doesn’t usually happen. PBIs are not of uniform size and the team has to create a deliverable product increment within the time box of a Sprint. So the team has to figure out what will fit and they may have to juggle the PBI ordering, and maybe even adjust some PBI content.

Tasks are often interdependent, and given the team’s knowledge of the current product state and of the domain, it might realize that it can save time by developing feature P before feature Q, or by doing task X before task Y.

The Scrum Team as a whole typically does not understand PBIs in enough detail to completely prescribe how the Development Team will implement them. In fact, design of PBIs to that level is waste because PBIs might queue up undeveloped for some time, and the business and team context may change over time, making all the work you have put into the PBIs irrelevant. Or other PBIs may find their way onto the Product Backlog, possibly deferring some PBIs indefinitely. But some design thinking is in order for the developers to consider how they will implement a given PBI. If they do this too early, then such plans may become out-of-date, and they don’t want to plan too late.

Development Team members may need to adjust their work plan during the Sprint as they come to understand more about business needs and technical constraints. This is difficult when working with large, monolithic PBIs.

Therefore:

At the beginning of every Sprint the Scrum Team (or all the teams that together deliver a jointly developed product increment) meets to plan how it will create value during the Sprint. The team agrees to a Sprint Goal and creates a plan for what the Development Team will develop and how the team will develop it. This requires that the Scrum Team do a detailed enough design of the solution to have a high degree of confidence about how to build the product, and requires that team members feel they can complete their work plan during the Sprint (see Granularity Gradient).

Sprint Planning is the initial activity in a Sprint. It is the transition along the Value Stream between the Product Backlog and the Development Team’s work plan.

During Sprint Planning, the Scrum Team creates the Sprint Goal and produces the initial version of the Sprint Backlog. An incidental output is an updated Product Backlog. If the Product Backlog is not yet a totally refined backlog at the beginning of Sprint Planning (perhaps because the Product Owner has added new items near the top of the backlog since last meeting with the Developers), then the Scrum Team discusses, estimates, breaks down, and orders the new PBIs to prepare for the work plan of the imminent Sprint.

The main activities of Sprint Planning are for the team to ensure the Product Backlog is ready (see Definition of Ready); to come to a consensus on a Sprint Goal; to select the PBIs the team forecasts it can deliver this Sprint; and to plan how to do that work and achieve the Sprint Goal. Most teams find it best to do these activities concurrently—for example, figuring out how to do work helps you understand its scope and effort required (velocity can be effective for forecasting the amount of work that the Development Team can complete in a Sprint; see Notes on Velocity ). That, of course, influences how much the developers can complete in a Sprint.

It is important that Sprint Planning allow time for enough design to create a well-understood Sprint Backlog. But the planning should be time-boxed. A rule of thumb is that the event should take no more than four hours for a two-week Sprint and proportionally less for shorter Sprints. If it takes longer, it takes longer—but seek kaizen opportunities to reduce the amount of time to plan and to correspondingly increase the time spent on building product.

If the Product Owner has not sufficiently specified a PBI for the Development Team to design its associated Sprint Backlog Items, the Development Team should not accept it for the Sprint (see Enabling Specification or Definition of Ready). Inadequately specified PBIs are a major cause of effort bloat and subsequent Sprint failure. Jeff Sutherland reports on one Scrum Team that had a standing rule that if PBIs were not sufficiently specified, the team would all go to the beach. (This sent a clear message to the Product Owner about the Product Backlog!)

A key output of Sprint Planning is that the Development Team should be able to explain how it can accomplish the Sprint Goal. If they can explain their work, it’s a good sign that they have discussed it to a good level of understanding, which raises the probability that the team actually can do it in the amount of time they estimate. A team might consider this as a measure of the effectiveness of the meeting.

As noted above, Sprint Planning produces the initial version of the Sprint Backlog. This is the initial plan the Development Team works from in the Sprint, which it refines and adjusts every day at the Daily Scrum. The Daily Scrum is primarily a daily re-planning event.

✥ ✥ ✥

The quality of Sprint Planning strongly influences the success of subsequent Daily Scrum events. If the Sprint Goal and Sprint Backlog are well-defined and understood, the Development Team is likely to have effective Daily Scrums, and any required replanning will be clear. A poor Sprint Planning activity may increase the burden on recurring Scrum of Scrums doing multi-team development.

The obvious outputs of Sprint Planning are the Sprint Backlog and the Sprint Goal. But Sprint Planning also strengthens the Unity of Purpose, and helps the Development Team and the Product Owner better understand each other’s needs and motivations. This strengthens the Community of Trust, and cultivates Fertile Soil.

The team polishes the backlog not only to strive for the Greatest Value but out of sheer Product Pride.

Picture credits: Image Provided by PresenterMedia.com.