...you have Stable Teams that are also Collocated Teams.

✥ ✥ ✥

Every culture has rhythms, such as holidays, that have nothing to do with the Gregorian calendar, yet most business cycles are based on the latter. Religious holiday vacations tend to pop up at seemingly random dates, but in fact often follow a lunar calendar: Ramadan, Passover, Easter, and Hanukkah are typical examples. We as professionals tend to believe that time is uniform, that a day is a day and a week is a week, yet Project Managers learn that they should treat December as a month with only ten days of effective work. In the meantime, the reality of local holidays confounds the fixed, internal units of time that come from the Gregorian calendar and are the foundation of Scrum Sprintss. And “local” differs from culture to culture and country to country. Denmark shuts down for the month of July; Germany tends to split its summer siesta across two months. Australia’s holiday season is different yet again, and heaven help the poor enterprises that believe in multisite development and which have locations in both Europe and Australia. We won’t even mention India, whose holidays follow the sun and the moon.

While we acknowledge the rhythm of the Sun in the Daily Scrum, we often ignore larger rhythms of life like the phases of the Moon and the local seasons. Human beings are not machines who can deliver the same every hour and day all time of year, just as European Project Managers deeply discount December. So we work in day time and sleep at night. We have weekends, holidays, and vacations. These create annoying irregularities for Sprint Planning and for the team’s velocity.

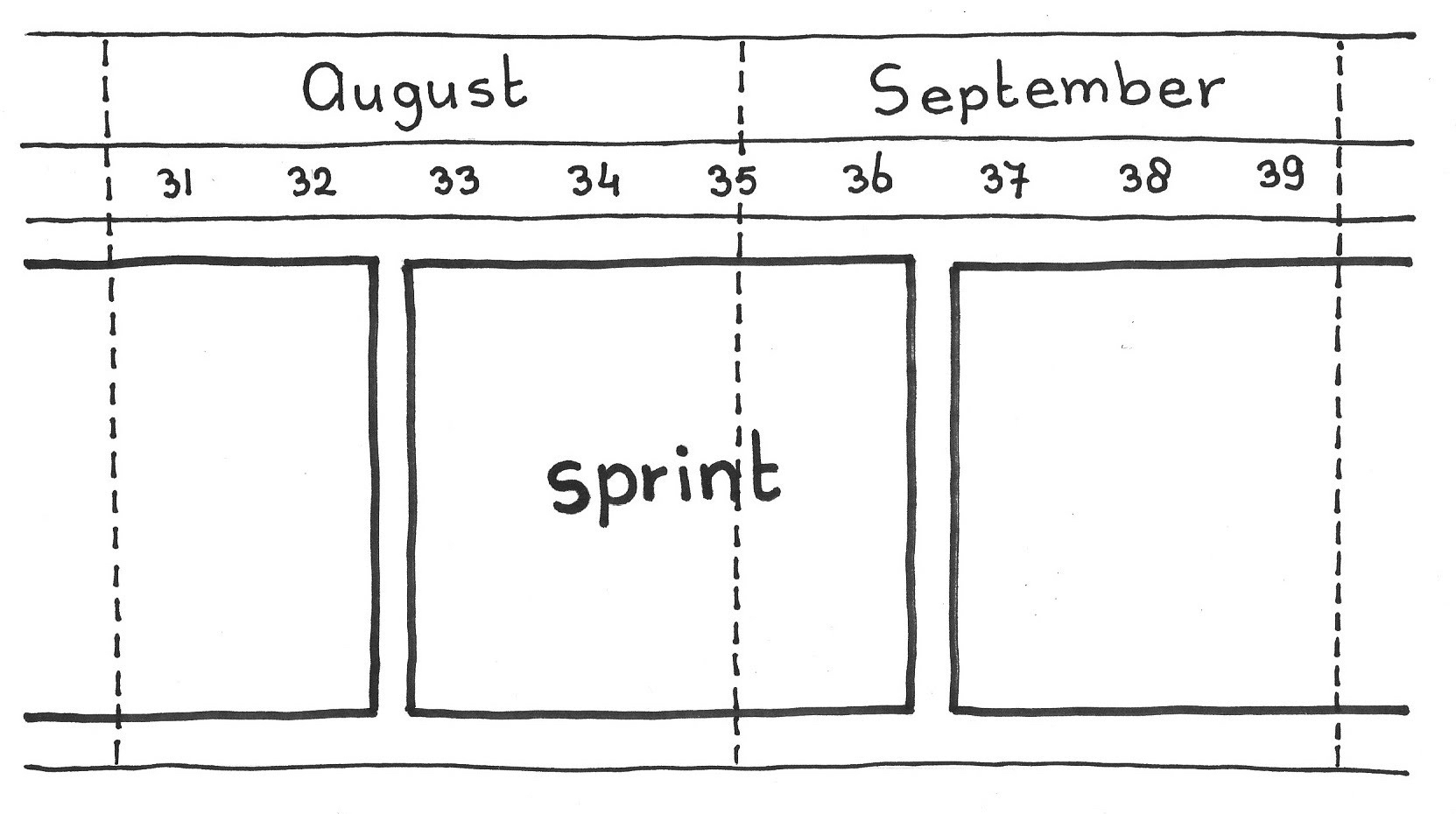

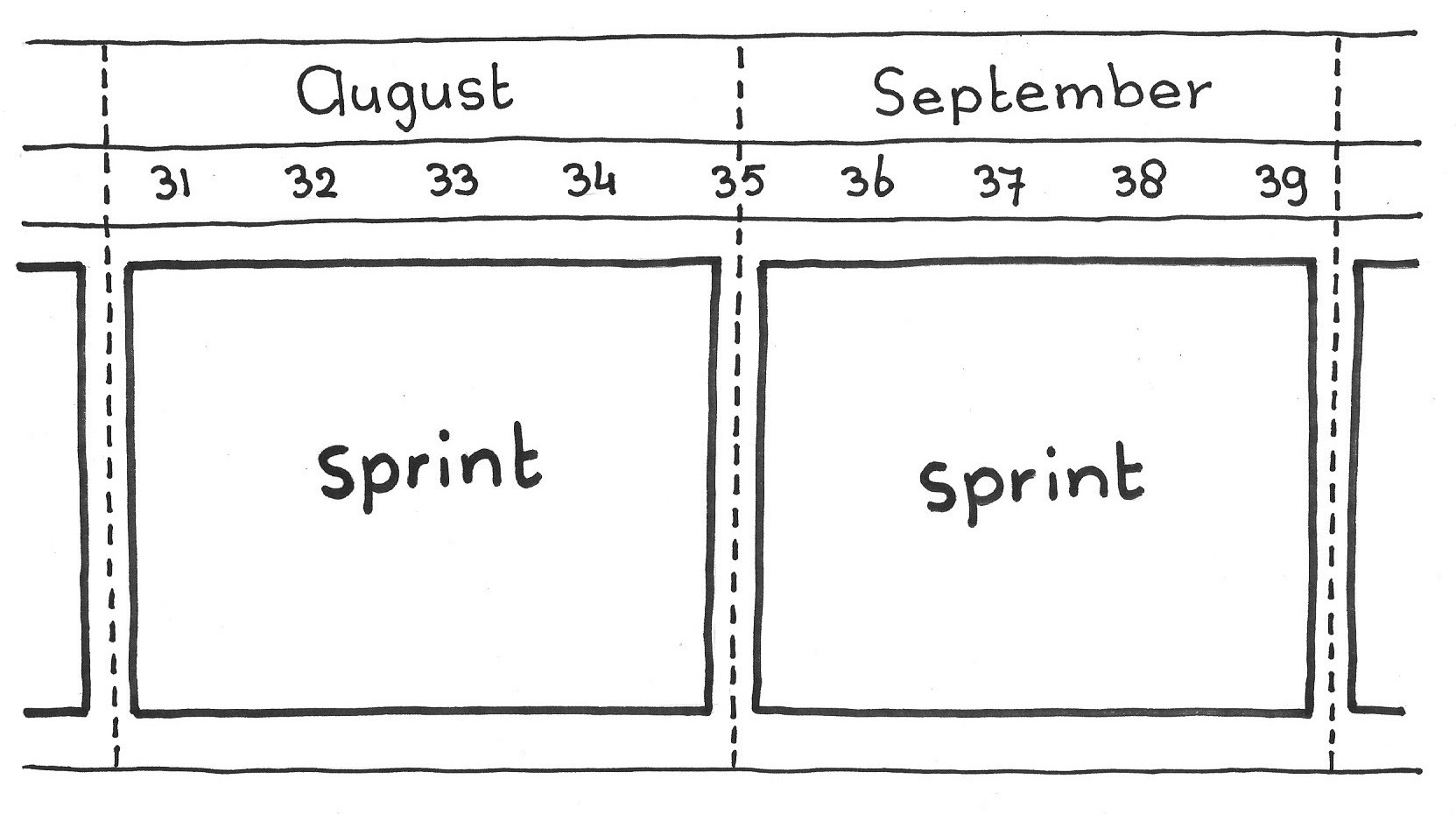

Early definitions of Scrum recommended that Sprints run on roughly monthly cycles; more specifically, on four-week cycles. In most cultures a Scrum “month” is not a calendar month. In monochronic cultures ([1]), we can define a day to be 86,400 seconds, and an “ideal month” is a collection of thirty such days. But these “months” are not the calendar months that vary in length: Sprints are always the same length. Scrum scheduling more closely follows the cultural rituals of the Scrum framework than it does any business calendar. (If you don’t believe this, quickly answer how many business months you have in a year and then how many Sprints you have in a year, hopefully without having to do any math.) So we can define cadences in Scrum in terms of ceremonies, rituals, and benchmarks from the framework rather than from the calendar. And the recommended Sprint length from Scrum’s early days was closer to the periodicity of our largest astral body than to the rhythms of the Gregorian calendar. (Today, two-week rather than four-week Sprints are the norm.)

Working outside natural rhythms upsets human subjects so badly as to suggest it has been the cause of numerous disasters such as Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, and the Exxon Valdez ship accident and oil spill ([2], p. 85).

Therefore,

Define Sprints with beginning and ending boundaries falling on the new moon and full moon. This creates a cadence that perfectly fits two-week and four-week Sprints. Use common sense when accommodating non-lunar local events such as Christmas, mid-summer, Thanksgiving, or other work pauses that are customary to the local culture. It can be a nice picture of incremental work.

Get the team involved in putting together a long-term Sprint calendar that accommodates holidays and traditional vacation times. For example, many European subcultures take vacation together during the same two weeks or month.

Those cultures that follow the Hirji calendar (altaqwim alhijriu) or other lunar calendars are already halfway there. Many of the religious holidays that otherwise upset the normal Gregorian cadence also follow a lunar calendar, and the chances that they align well with Sprint boundaries is much higher if you Follow the Moon.

✥ ✥ ✥

This scheduling establishes a regular cadence, and universally sets expectations about when the next Sprint will end. The team can synchronize delivering Regular Product Increments with broadly understood cultural rhythms. Team members’ energy cycles will likely conflict less with naturally occurring cycles in the culture. This helps the team advance some of the deeper human nuances of Greatest Value.

This is a “Ha” (<0XE7><0XA0><0XB4>—“break the rules”) pattern, for advanced Scrum practice. For “Shu” (守—“by the book”) use Fixed-Date PBI. In “Ri” (離—“expertly extemporaneous”) we can playfully conjecture that you are enough harmonized with your environment that you might follow the moon naturally.

Use common sense in dealing with holidays. One way to deal with the way that holiday seasons irregularly cut across the lunar calendar is to package them as Product Backlog Items: see Vacation PBI.

Sally Helgesen ([3], p. 140) writes about the importance of natural cycles to well-being:

The sociologist Eviatar Zerubavel, in a fascinating study entitled Hidden Rhythms, observes that humans experience time in two entirely different ways: as the cyclical rhythms of nature, governed by recurrent seasons; and the repetitive rhythms of the machine, regulated by schedules, calendars, and clocks. He notes that being able to perceive time as cyclical is essential to our well-being, a crucial manifestation of our connection with nature in which time always moves in cycles.

See also Sprint.

[1] Edward T. Hall. The Dance of Life. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, re-issue of 1988.

[2] Steven H. Strogatz. Sync. New York: Hachette Books, 2004, p. 85.

[3] Sally Helgesen. Everyday Revolutionaries: Working Women and the Transformation of American Life. New York: Doubleday, 1998, p. 140.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.