…you are reaching the end of a Sprint, and are getting ready for the next one. Naturally, no matter how well it went, you would like to improve.

✥ ✥ ✥

Over time, without explicit attention, processes and discipline tend to decay. People get sloppy. Making isolated process changes without due focus feeds entropy, but without periodic change the team misses opportunities to increase value.

You want to continually improve. The Daily Scrum gives the team a chance to examine itself and improve the product direction on a daily basis. However, it is not a forum appropriate to re-chart the process for several reasons.

First of all, there is daily variation in performance, and it is pointless to make adjustments in response to what are just normal process variations. A single day (from one Daily Scrum to the next) is often too short to see whether a change really results in the desired improvement, and changing processes in the middle of the Sprint is disruptive at best. Second, the focus of the Daily Scrum is inspection and adaptation to achieve the Sprint Goal. Thus, the horizon is very short-term, and the Development Team is focusing on completing its work rather than on systematic team issues. A third reason is that in the heat of battle (in the middle of a Sprint), you are likely to get only one or two perspectives on a problem, rather than a full appreciation of most contributing factors. It is dangerous and inappropriate for the team to draw conclusions from incomplete information.

At the Sprint Review, the team reviews the product with the stakeholders. This event is not the place to analyze problems and to propose improvements, but to rather focus on the product. The Development Team and the Product Owner should take ownership of these problems as a Self-Organizing Team and determine how to deal with them outside the Sprint Review, without the stakeholders. The product focus of the Sprint Review rallies the team and stakeholders around one-time problems. Yet, it is even more crucial in Scrum to explore the recurring process patterns that contribute to problems that seem independent and unrelated, but rarely are.

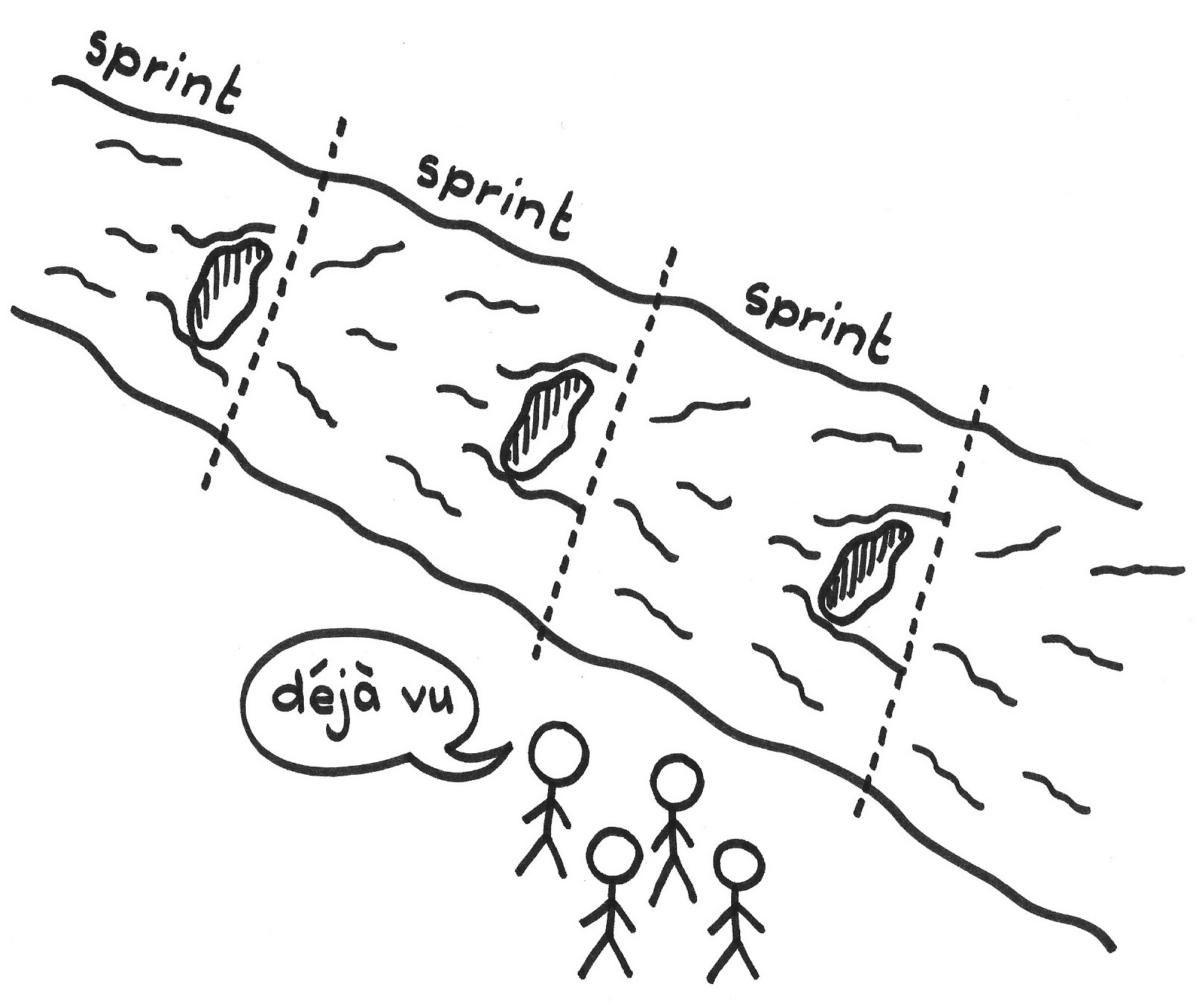

Since Sprints come one after another, there is a tendency to rush from one Sprint right into the next, with little or no thought about how the team completed (or not) the work. This leads to doing the same things over and over, making the same mistakes.

Having made several improvements over previous Sprints the Scrum Team might become convinced they are doing a good job and that there are no new improvements to be found (“This is just the way how we work!”). The added value of improving seems to decline and the team may therefore view it as a waste of time (“We are already very busy doing real work!”).

When a team examines itself, it makes its members vulnerable to criticism. Individuals might feel embarrassed, threatened, or incompetent. This can lead to defensive behavior in which team members can deny their own responsibility, both individually and collectively, and externalize the problem ([1]).

Therefore:

At the end of each Sprint, have an event where the Scrum Team can assess how it performed its work during the Sprint.

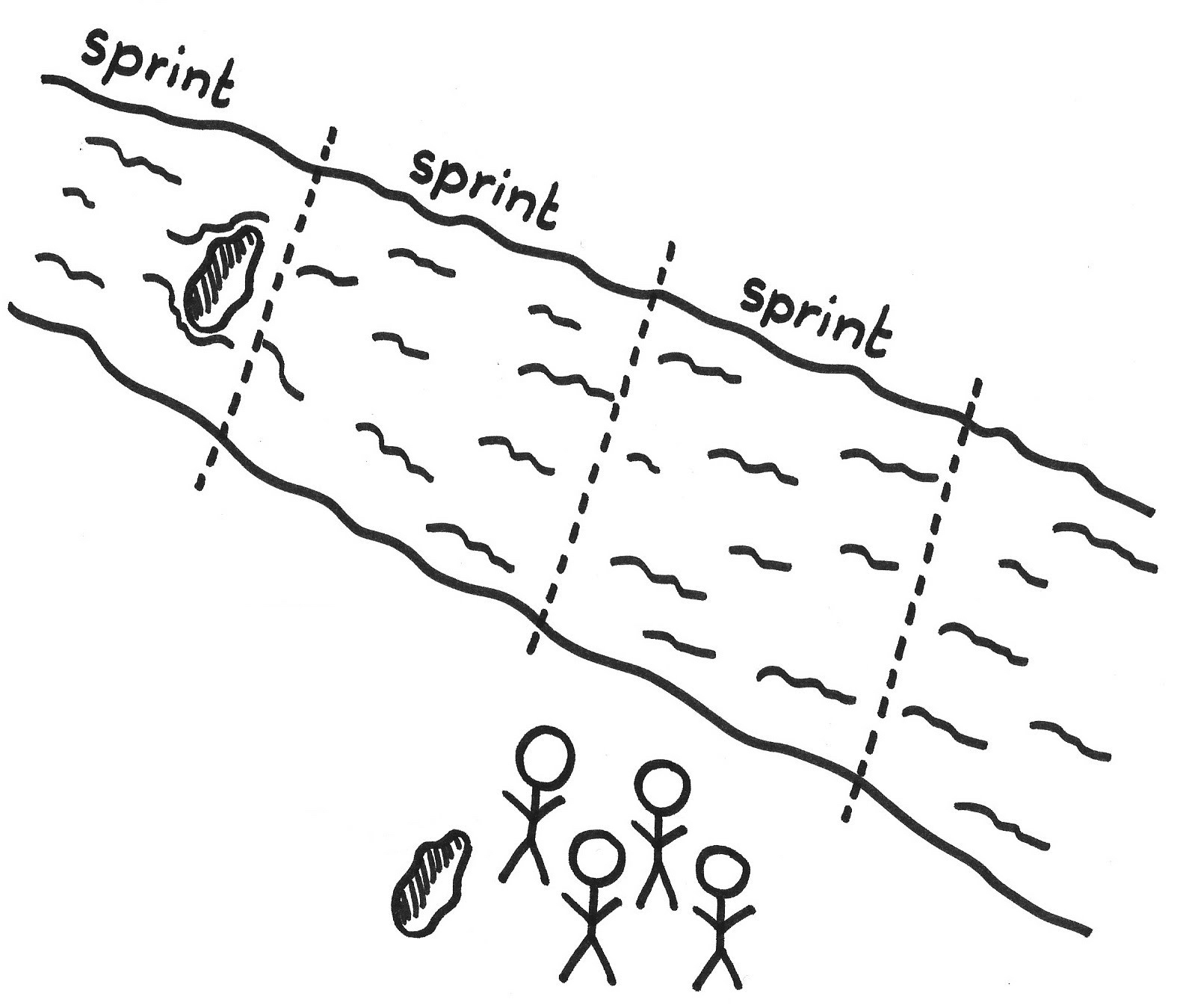

Hold a Sprint Retrospective at the end of the Sprint. This is a natural time for reflection. Examining completed work unveils a full system perspective (where the system is the team and its processes). Taking stock of how one is doing while in the middle of a process gives only a partial picture, and from a very limited perspective. So we align retrospectives with completion of work—at Sprint boundaries. In addition, the challenges and triumphs of the Sprint are still fresh in everyone’s minds.

The team proposes process changes in the interest of achieving Greatest Value. A process change can relate to people, relationships, process, environment, or tools.

✥ ✥ ✥

Scrum has its roots in the Toyota Production System (TPS), which has process improvement at its heart. In the TPS manual we find the instruction, “Checking is about hansei.” Hansei is a deep form of personal or collective regret for having failed. A good Scrum Team does hansei over its failures, and then redirects the energy of regret for the failure into positive energy for fixing the problem; see Scrumming the Scrum. The Sprint Retrospective is therefore also a time of healing and renewal for the team. The lean community considers Taiichi Ohno to be the founder of the TPS. A famous quote commonly attributed to him is:

No one has more trouble than the person who claims to have no trouble. (Having no problems is the biggest problem of all.) [2]

Focus on developing a culture where the Sprint Retrospective becomes an integral part of every Sprint. Build it into the regular cadence of the team. Avoid the temptation to skip it because you feel you need the time to complete the last of the Sprint’s work. This would reinforce a cultural belief that Retrospectives are not really important.

Time-box the meeting. Allow enough time to explore issues in some depth, but don’t make it so long that people get bored. Scrum recommends no longer than a three-hour meeting for a one month Sprint. The meeting is usually shorter when the Sprint is shorter.

Normally, the entire Scrum Team should attend, including the Product Owner. On rare occasions, if the Development Team members feel that the Product Owner dominates the conversation or otherwise suppresses frank and open discussion, they might ask the Product Owner not to attend. Note that this is likely a sign of larger problems. Because Scrum is a framework that helps remove problems to achieve ever-greater value, and since the Product Owner is at the heart of the value proposition, trusted participation of the Product Owner in these meetings is key to long-term success beyond any superficial measure.

One principle of the Agile Manifesto [3] is to have regular Retrospectives:

At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

Retrospectives, especially regularly scheduled ones, can easily become superficial meetings that explore no substantive issues. To deal with this, use known effective methods of Retrospectives, such as cataloged in [4]. For example, one method is to identify things that went well, ongoing problems, and specific things to do ([5], [6]). Consider varying the method from time to time. Base the discussion on empirical insight. In particular, examine such concrete indicators as percent of the Sprint Backlog completed and team velocity. Furthermore, identify specific process changes that the team will make during the next Sprint.

Priority-order the planned changes in the Impediment List. The pattern One Step at a Time recommends that the team make a single change at a time, so they can understand how each change contributes to improvement; see also Scrumming the Scrum. The pattern Happiness Metric suggests embracing the change that would most increase the team’s passion and sense of engagement. Also, be sure that you can measure the benefits and liabilities that the change brings about: its cost, benefits, and disadvantages (see Testable Improvements).

Consistent use of a Sprint Retrospective does not guarantee process improvement or even process stability. Though it’s not sufficient to just do Retrospectives, it’s probably necessary to regularly bring the issue of kaizen mind to a focus (see Kaizen and Kaikaku). Done right, Sprint Retrospectives encourage the team and give them pride in being able to improve over time; see Product Pride.

Retrospectives can easily degenerate into whining sessions. In order to combat this problem, go into the Retrospective following Norm Kerth’s prime directive: “Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand” (“Retrospective Exercises,” Chapter Six of [6]). This requires a community such as the one described in Community of Trust. Also, make the team aware of what they themselves can change and what they cannot change in the short term, or maybe not at all ([7]). Furthermore, identify both good things (“nuggets”) and problems. Don’t just look at the bad. Some of the good things may be worth writing down. For example, a written Definition of Done should grow as the team discovers and learns new techniques for getting to Done (see Definition of Done). Whining can also indicate deeper issues, and the ScrumMaster should be attentive for cues of deeper problems in the overall tone of the Retrospective event.

Note that Retrospectives of just two or three hours are typically insufficient to explore deep issues. Sprint Retrospectives are therefore somewhat of a compromise between depth of discussion and length of the meeting. A problem found during the Sprint Retrospective might owe to deeper, complex relationships that the group cannot properly surface and explore in just three hours. An experience report from Jeff Sutherland based on a communication he had with the Investment Group notes the following:

Impediments are like mosquitos. You swat one and 25 come back. So, you need to get the root-cause. What you have to do is drain the swamp to get those mosquitos to stop coming.

In order to “drain the swamp” you can consider working at the level of double- or even triple-loop learning as described by Swieringa and Wierdsma ([8], pp. 37–42). In short: single-loop learning is about changing the rules and double-loop learning changes the underlying structure. Triple-loop learning deals with the essential principles and values at the organization’s foundations and history. Norm Kerth suggests taking three days to explore the deep structural issues in an organization, and he has proposed a framework for three-day, off-site Retrospectives that drive to this level of improvement ([6]). The extensive Retrospective of Kerth is more suitable for dealing with deep vulnerabilities of the team because it invests more time to create trust between team members than in the relatively short Sprint Retrospectives. It also enables deeper kaikaku (discontinuous) changes beyond the incremental changes which are usually the focus of a Sprint Retrospective.

The Skype audio-visual engineering team, responsible for Skype’s high-quality audio and video at the time and also for codec development, held occasional two- to three-day off-site meetings in conjunction with their Team Sprints. These events led to new inventions, redesign of their own workspace, and development process innovations. [9]

[1] Chris Argyris. “Teaching smart people how to learn.” Reflections 4(2), 1991, https://www.ncsu.edu/park_scholarships/pdf/chris_argyris_learning.pdf (accessed 2 November 2017).

[2] Taiichi Ohno. AZQuotes, Taiichi Ohno Quotes, http://www.azquotes.com/author/44597-Taiichi_Ohno, n.d., (accessed 11 July 2018).

[3] —. Manifesto for Agile Software Development: Principles. Agilemanifesto.org, http://agilemanifesto.org/principles.html, 2001, accessed 23 January 2017.

[4] Esther Derby and Diana Larsen. Agile Retrospectives: Making Good Teams Great. Raleigh, NC: Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2006.

[5] Alistair Cockburn. Agile Software Development, 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, Oct. 2006.

[6] Norm Kerth. “How long should a retrospective be?” In Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Reviews. New York: Dorset House Publishing, 2001, ff. 53.

[7] Stephen R. Covey. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Simon & Schuster, 1992.

[8] Joop Swieringa and André F. M. Wierdsma. Becoming a Learning Organization: Beyond the Learning Curve. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1992, pp. 37–42.

[9] Personal communication with Mark Gillett, former Skype COO, 22 February 2019.

Picture credits: Image from: M.C. Escher's “Hand with Reflecting Sphere” © 2018 The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands. All rights reserved. http://www.mcescher.com.